Introduction

Local British newspapers reported daily on the Bangladesh Liberation War during the whole nine-month-long conflict. The war started in late March 1971 and ended on 16 December of the same year. The purpose of this section is to give a flavour of the war and how local newspapers kept the British people informed. Rather than providing a comprehensive account of these reports, it looks at one or two reports per month.

First three months: April - June 1971

'Resistance in East Pakistan Crumbles Fast’

About two weeks into the war, on 13 April 1971, the Coventry Telegraph ran a headline called 'Resistance in East Pakistan Crumbles Fast’. It reported that ‘columns of President Yahya Khan’s Pakistan army’ were ‘fanning out in all directions'. They were 'swiftly advancing' and 'causing the resistance of the ‘Break-away East Pakistan’ to crumble.

According to the newspaper, a ‘reported shipment of Indian arms to the secessionist forces' would be unlikely to 'prolong the... the liberation'. From the perspectives of the newspaper, there was very little sign of ‘preparations for a lengthy guerrilla campaign’.

The newspaper reported the fears of many prominent Awami League leaders of a prolonged conflict. If that were to happen, they thought, the liberation war will ‘inevitably fall under the communist leadership’. One reason cited was that the communists have a tough discipline and they are 'backed by Marxists in neighbouring India’.

‘Bitter fighting in East Pakistan’

On 14 April 1971 the Reading Evening Post, based on information from the Press Trust of Indian, reported that there was 'bitter fighting’ in East Pakistan. There were some losses, some gains and some positions still controlled by the Bengali liberation forces.

‘Pakistan troops had gained control of two towns while Bangla Desh liberation fighters had captured the jute centre of Sylhet. Pakistani Air Force planes bombed and strafed Bengalis as they fought for Sylhet’. But they were 'forced to withdraw to Shalutikor airfield five miles away’.

The Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, was asked about the “open support” of Pakistan ‘announced by China'. She said that this ‘would not deter India from her stand on the issue'. On the question of India recognising ‘Banga Desh', she said, 'the matter would receive due consideration’.

According to the Free Bangla Desh Radio, the ‘Prime Minister of the provisional Government, Mr Tajuddin Ahmed said that: “Our resistance has created a new and bright example in the history of freedom movements. It is an example for all”.

‘Mediaeval butchery in East Pakistan’

Three weeks into the war, on 16 April 1971, the Belfast Telegraph reported an Indian Government official who accused ‘Pakistan of indulging in “savage and medieval butchery” in East Pakistan'. This was in response to certain Pakistani media broadcasting that 'indulged in “false and fallacious propaganda” against India’.

He thought that Pakistan was trying to divert the attention away from what they were doing in East Pakistan to present it as a dispute between India and Pakistan. They would fail to ‘persuade the world' that there was 'no struggle by the 75 million people of East Bengal'. He described the Pakistani action as ‘pre-planned carnage and systematic genocide in East Bengal’.

‘30,000 Migrants Believed Killed’

On 8 May 1971, Belfast Telegraph reported on the non-Bengali victims of the war. They were identified as Biharis who only recently arrived in East Pakistan during the partition of India violence. The welcome they received early on did not last long. When the war started, they became the target of hate. Many Bengalis considered them to be Pakistani collaborators.

The newspaper reported that about 30,000 non-Bengalis were believed to have been killed across East Pakistan since 1 March 1971. Most of them were said to be ‘Moslem Biharis… but many Hindus were also reported massacred’. About ‘90 miles from Dacca,’ a systematic slaughtering ‘between Bengalis and non-Bengalis’ was reported. This ‘left many thousands dead before the order was restored’.

Based on an account of a survivor who told ‘newsmen’ that out of 5,000 non-Bengalis where he lived there were now only ‘25 survivors’. The soldiers who brought the survivor denied ‘that women and children were knowingly killed by soldiers'. But said that 'hundreds of men were killed in the fighting since 26 March’.

The survivor showed his neck wound to the newsmen and described ‘where he said Bengalis shot him through the throat before knifing him and dumping him in the river'. While he was describing how his sister’s breast was mutilated before she was killed, he broke into tears'. He was led away by soldiers who had brought him to speak to the newsman.’

‘Cholera Strikes Again in Bengal’

On 17 June 1971, the Coventry Evening Standard reported that ‘Cholera Strikes Again in Bengal’. This new cholera infection was said to have broken out in a new place in West Bengal as refugees continued to pour out of East Pakistan and into India. Cholera was ‘raging in Burdwan district near the industrial town of the same name, 55 miles north-west of Calcutta’.

The refugee flow that was ‘halted for about 12 days’ had started again. The authorities had earlier announced that they had 'brought the cholera epidemic under control that had already killed 5,000 people'. The new inflow of refugees has not reached the magnitude of ‘the mass flight last month when about 100,000 people crossed into India each day’. India was sending ‘six ministers around the world to seek more aid for nearly six million refugees’.

The mid three months: July-September 1971

'India Accuses U.S. Over Supply of Arms to Pakistan'

On 13 July 1971 the Belfast Telegraph reported India's strong opposition to the decision by the 'United States... to supply Pakistan with a total of 35 million dollars of military equipment’. Mr Swaran Singh, the Indian Foreign Ministers, considered such action by America ‘in the present context amounted to condonation of genocide in Bangla Desh'. And he ‘left the United States Government with no doubt about the dangerous implications of such a policy’.

According to a ‘highly placed diplomat', the 'Americans have decided to continue to supply Pakistan with arms'. They believe that they will be able to continue to talk to President Yahya Khan and persuade him to accept a realistic political settlement’.

‘Bengali hearts are with Bangla Desh’

On 17 August 1971, the Aberdeen Press and Journal published a piece called ‘Bengali hearts are with Bangla Desh’. The newspaper's London staff, Ralph Shaw, went on ‘a fact-finding tour' of the divided Pakistan. He wrote that when he was talking to a UN official at the Intercontinental Hotel, he was told that he would be safe there as it was heavily guarded. But this sense of safety was an illusion. It got shattered very soon by the bombing of the ‘men’s lavatory’ by a ‘plastic’ explosive, which also ‘practically destroyed the spacious lobby’.

When he went around the city, he observed fear everywhere. He wrote that ‘recently there was heavy fighting between the Pakistani Army and the East Bengal secessionists. Many people, including a shop keeper and a Bengali government official, also whispered in his ears, “we want Bangla Desh”, and “don’t believe what they say. They all lie… We want Bangla Desh” ‘.

His roaming of 'Dacca' also took him to the old part of the city. He walked ‘alone in the… narrow, muddy tracks' with 'bullock carts, cows, donkeys, dogs, beggars and the ubiquitous open-faced shops'. He described the place as 'the home of the poverty-stricken masses’.

Ralph Shaw saw ‘Dacca’ at night ‘deserted apart from the police and army patrols’. He observed that the ‘Liberation Fighters’ had ruined the ‘cooking facilities at the Intercontinental recently by blasting the strategic gas pipeline into the city’. They also blew 'up a generating station’, which had ‘plunged a large part of the town into darkness'.

He judged that if left alone the ‘Bengalis' were 'no match for the Pakistani army’. But then it would become a colonial rule on British pattern for the foreseeable future. As West Pakistan largely depended on draining resources from the East Pakistan economy, he thought, President Yahya Khan would do whatever he can to ‘preserve the integrity of what now a geographical absurdity’.

Photo credit: The Aberdeen Press and Journal, 17 August 1971: Bengali hearts are with Bangla Desh.

Image/article courtesy of https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

‘Honeymoon became nightmare’

On 17 September 1971 The Kent & Sussex Courier ran a story on how a honeymoon became a nightmare for a newly married couple. Mr Martin Crorie who owned an Indian restaurant called Mumtaz in Tonbridge ‘got married to his childhood sweetheart’. Her name was Dolly, and she was twenty years old at that time.

The paper said that they got married in October 1970, but it was only now that the ‘military government in Pakistan finally allowed them to leave their own country’. This suggests that the couple were both East Pakistanis. If so, Martin must have been to the UK earlier, set up a business and gone back to East Pakistan to marry his childhood sweetheart, Dolly. But this is speculation as the newspaper provides no details about their origin.

The couple reported that they had encountered horrific scenes while trying to flee the ‘avenging West Pakistani troops sent to subdue the breakaway East Pakistan’. This included ‘young children bayoneted, houses burned with families inside, teenage girls violated and murdered’. They faced questions from the army everywhere, saw ‘bodies on the roadside’, and learnt that some of the murdered were thrown into the rivers.

With the ‘aid of influential friends', eventually, they got a flight from Dacca and Karachi’. There was a final act before they could leave East Pakistan. They had to promise that they ‘would not spread unfavourable propaganda about the army’ when they got back to ‘England’.

The last three months: October-December 1971

‘Pakistan massing forces claim’

On 16 October 1971, the Coventry Telegraph reported that there was an increase in tension along the border between India and Pakistan. Border areas has been experiencing ‘constant artillery attacks for the past fortnight’. A Pakistani 'official... in Dacca' announced that this resulted in civilians from border areas ‘moving to regions deeper insider Eastern Pakistan’. It was also announced that Indian shelling so far has ‘killed 38 villagers and wounded 57 in 34 border villages’.

India ‘said that Pakistani forces appeared to be massing on the border’. This was two days after Mrs Indira Gandhi, the Indian Prime Minister, ‘accused Pakistan of threatening to go to war with India’. ‘Pakistani forces had moved closer to the Indian border in both East and West Pakistan', and 'there were indications of a large-scale military build-up in the last few days’. The Indian Defence Ministry said that they were ‘taking necessary precautionary measures’.

'15-hour curfew in capital’

On 18 November 1971 the Reading Evening Post ran a headline called ’15-hour curfew in capital’. The curfew was designed to deal with the ‘apparent escalation of guerrilla attacks’ in the city. The guerrillas aimed at a range of targets, including shopping centres, mosques, schools, commercial buildings, public utility and industrial complexes.

The curfew sought to comprehensively comb the city to stop the ‘sympathetic population’ supporting the guerrillas to slip through the net. As such, on 17 November 1971 troops went ‘house-by-house in search of Bangla Desh guerrillas and arms’. Pakistan radio reported that ‘138 people were detained and four killed when they “resisted arrest”, and that 'people were co-operating in pointing out “miscreants”. The city's population 'had been told to place arms and ammunition in front of houses and no questions would be asked’.

‘Indians Invade Pakistan’

On 4 December 1971 Aberdeen Evening Express reported that India had invaded Pakistan earlier on the same day.

The commander of the Indian forces, Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Arora, said that they had two purposes. To ‘force the surrender of the 80,000 Pakistani troops in the area and establish an independent government of Bangla Desh’. They had orders to attack ‘enemy warship and cut lines of communication between East and West Pakistan’.

Yahya Khan, the ‘West Pakistan President’, said to his people that ‘the present war will be the final war with India’.

The newspaper reported on both sides and perspectives of the war. General Arora had been set no limit on ‘his operations’. But his order was not to ‘cause unnecessary damage to the infrastructure of East Pakistan’. President Yahya Khan said that ‘his country was fighting for its integrity and honour’. He believed that God was on Pakistan’s side in the face of the enemy, the Indian Government, who launched a ‘full-scale war’ on Pakistan.

‘Indians take key towns in the east’

The Coventry Evening Telegraph reported on 7 December 1971 that ‘Indian forces today overran the Pakistani military base at Jessore and captured strategic town in Sylhet'. Jessore was about 80 miles from ‘Dacca’ and contained ‘one of the province’s three main military bases'. It was the 'first major East Pakistan town to fall to India’.

Indian naval aircrafts attacked 'the ports of Khulna, Chalna and Mangla'. They destroyed 'two gunboats' and damaged 'two others’. Pakistan ‘admitted that troops had vacated their position in Benapol’. Their ‘troops were trying to establish alternative positions’. At the same time, sources in India reported that Pakistani troops had ‘launched a “massive attack” on the Kashmir front’.

President Yahya Khan had asked Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of West Pakistan and ‘Nurul Amin, a right-wing East Pakistan political leader, to form a coalition government. Meanwhile ‘a UN spokesman in New York’ reported that ‘military planes had attacked a Canadian C130 Hercules transport’. It was sent to see if it was safe to land in ‘Dacca’ airport to evacuate ‘265 diplomats and officials’. UN efforts ‘to get a ceasefire’ proved unsuccessful.

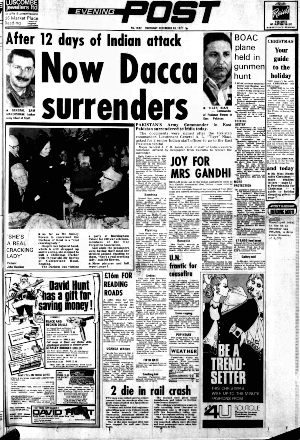

‘After 12 days of Indian attack, Now Dacca surrenders’

On 16 December 1971 the Reading Evening Post reported that the surrender documents signed after the Pakistan commander, Lieutenant General A. L. “Tiger” Niazi, asked for a senior Indian staff officer to go to the capital of East Pakistan. ‘Major General J. F. R. Jacob, chief of staff of India’s eastern command, arrived by helicopter from Calcutta to receive the surrender'.

Joy for Mrs Indira Gandhi

The newspaper reported that ‘Bedlam broke out in the Indian Parliament today as Mrs Indira Gandhi announced that Indian troops entered Dacca this morning. Jubilant members of all parties jumped from their seats and started shouting and pounding their desks in glee’. At the parliament, ‘members from West Bengal, which has strong cultural ties with neighbouring East Pakistan, rushed to phones to order rasagula, the traditional Bengali sweet distributed on festive occasions’. They said, ‘when Dacca falls, we’ll start distributing’.

‘We'll regain East, pledges Bhutto’

On 21 December 1971 the Aberdeen Evening Express reported that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the new president of Pakistan, pledged to regain East Pakistan. In 'Rawalpindi shortly after taking power' he said 'East Pakistan would be regained and warned of “a house to house fight” if India tried to impose its will.

At a 'news conference following a nationwide broadcast' Bhutto promise 'to restore democracy’. He described ‘West Bengal, the Indian state bordering East Pakistan as a slum: my Bengal, East Pakistan, will not go to the slum of India’. At another point, he declared: “Half of our country is under foreign occupation, but we are not down and out. We will regain it.” Mr Bhutto said new ties must be established with East Pakistan no matter how loose’.

Photo caption :Reading Evening Post, 16 December 1971: After 12 days of Indian attack, Now Dacca surrenders

Image/article courtesy of https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/